Upping our skiing time from 10 to 11hours a day once we began our descent the distance began to noticeably improve. From struggling to hit 25kilometers per day we were now easily making 30-35. Soon a speck appeared on the horizon that gradually grew into the dystopian shape of DYE 2. Camping 10km from the station we knew we had reached a pivotal moment in the expedition. We had been on the same bearing for 330km and now would be changing direction to make our way off the ice. Leaving 10km to do the following day left us half a day’s rest and exploration at the now abandoned radar station.

(Strolling into Dye2, where’s the horizon??)

In the late 50s, DYE 2 was built as part of the DEW (Distant Early Warning) Line to provide warning should Soviet Bombers ever fly towards North America. It was an extraordinary feat of engineering and logistics, during it’s most intensive period up to 60 personnel were based here, with all the supplies and fuel having to arrive by plane. Storms would mean the Station would have to be closed from the outside and fully self-sufficient for weeks at a time. In the late 80s with the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the discovery that the station was sinking into the ice an immediate evacuation was ordered. Aside from the odd Mad Explorer it has been frozen in time since then. The snow rises approximately a meter each year and one day will claim this eerie, redundant, messenger of doom.

(Back in the day)

Arriving at Dye 2 we wasted no time in establishing our camp, we were eager to make the most of our afternoons rest as it was the last we would be getting until we finish our journey. Unfortunately, our insurance and permits did not cover us to go inside DYE 2 so obviously we both had to go and explore. Louis searching for the entrance along fell around 4 meters when the snow he was walking on gave way and he tumbled down to the foundations of the structure. Following his footprints, I jumped down where they disappeared and nearly broke my neck as well figuring it was a proper route. We must have looked like a right pair of lemmings.

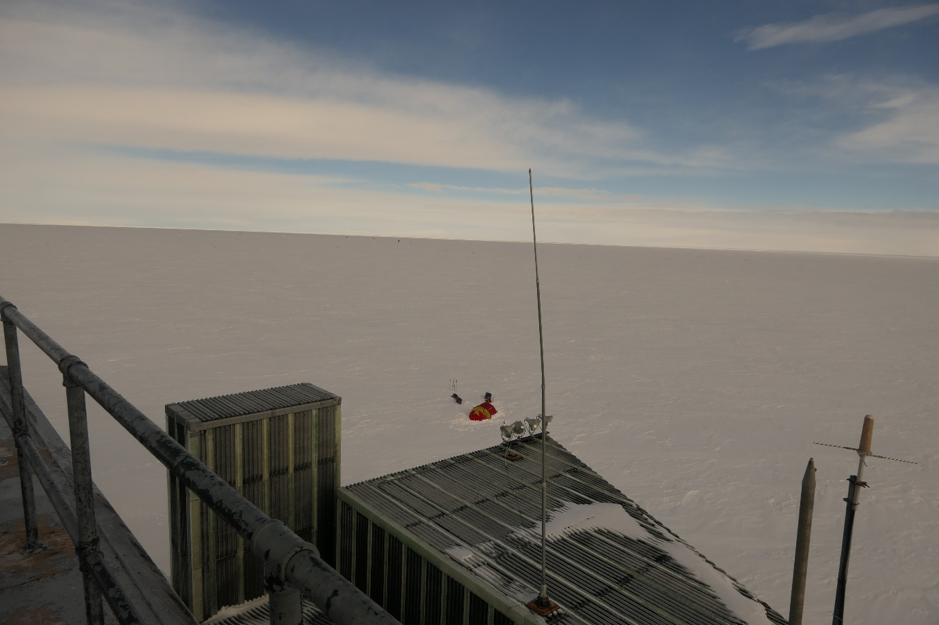

(and now)

Slipping and sliding carefully around the metal supports we soon found the entrance. The place truly was frozen in time; Magazines from the 80s with letters half wrote spoke volumes of the hasty nature of the evacuation of the station. Eggs still in the fridges, rations lining the stores along with plates of food frozen solid. The bar was still fully stocked with beer now frozen, we meandered through the base slowly exploring each nook and cranny. The basement had been claimed by the snow and ice and was completely inaccessible, as had some rooms where the windows had succumbed to a tempest. Flaking paint and patches of mould on the fresh food signified the time which had past, as did piles of rubbish left by previous expeditions, though other then this we could have still been in 1988. After definitely not looting some souvenirs we made our way to the golf ball like roof, where the behemothic radar dish was housed. Stepping out onto the balcony we were greeted by the arctic wind and soon made our way to the sheltered side looking in awe and the infinity of ice and snow that surrounded such a surreal location.

(inside)

Knowing this was our best chance of getting a fix on our phones for a while we called Lars for a weather update and were greeted by;

“Are you boys having fun exploring DYE2”

Followed quickly by;

“You should get your rest. Tomorrow it is hammer time”

Laughing at his quote we chatted over what we needed to do over the next few days. He told us the trip from Dye to the edge of the ice cap takes between 6-8 days depending on the group and conditions, before adding he had done it once in 4 days (Showoff). We have 7 days of food left and would need to have at least one day spare as we are doing the full coast to coast crossing which takes a day longer. If we are to come off the ice in 6 days, we were told we would need to start doing some much longer days. Sighing we once again resigned ourselves to the misery to come, we felt like we had been putting in 100% already and now were being told we needed to put in even more. Returning to the tent we discussed what was needed and decided on putting in an extra 2 hours a day which would mean 12-13 hours of skiing. With the time it takes setting up/breaking camp, melting snow and making food that would probably mean 5 hours of sleep a night for the next week. This would be some challenge. Hammer time indeed.

(view form the dome)

I had saved a pack of Oreos for when we reached Dye 2 as a reward, making ourselves one of our last remaining cups of tea each we divided the biscuits between us. After knocking my tea over and watching it disappear into the snow, I held back the grief by biting into a handful of crushed Oreos. The distinct taste of fuel filled my mouth and glancing at Louis I realised the same had occurred to him. One of the fuel bottles must have leaked contaminating the biscuits. They had been sharing the fuel bag so I didn’t see them and eat them, however it was a completely schoolboy error to do so. Ditching our morale into the snow, our spirits had gone from hero to zero, and now all we have to look forward to is a week of pain, hunger and tiredness. Onwards and upwards.

If you have enjoyed reading about our journey and wish to donate to the underlying causes behind Expedition 5, you can via the button below.

Anthony Lambert

Co-founder Expedition5

anthony.lambert@expeditionfive.co.uk

www.expeditionfive.co.uk